My first novel, slated for publication with David C. Cook in early 2014, involved hours and reams of research. I researched everything from fossils, to barbecue restaurants, the history of Haiti, pecan recipes, and more. I organized text, web links, and photos into dozens of Word documents, which I then had to flip open and closed while writing and editing each chapter. Add this to the half-dozen internet browser screens I had open for research, and, well, my computer was on the verge of crashing.

So was my brain.

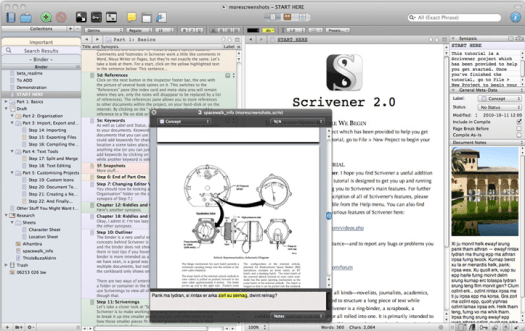

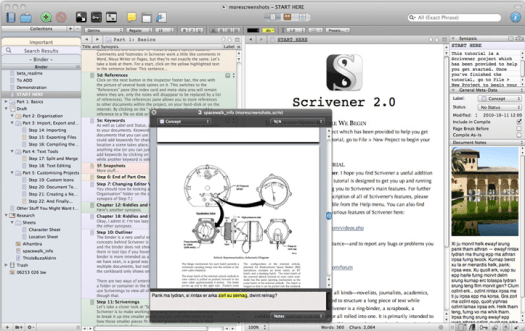

At the time I didn’t know any better, so I never lamented the process. But now that I’ve found Scrivener, a software program for writers of any genre, I marvel at how I ever kept my sanity. Currently neck-deep in an intense season of editing, I’m especially glad I can dump my manuscript in there, blow it up, and put it back together again with Scrivener.

Now, I will warn you. What you’re about to read may sound like an infomercial, but it’s not. I downloaded the trial version (highly recommended), quite skeptical about how much easier this could really make my writing life. But after just two days, I bought the software outright. First of all, this little slice of computer engineering GENIUS only cost $45—a small price to pay for sanity. An even smaller price to pay for the time it’s saved me, and the fun it brings to the novel writing process.

What’s so great about Scrivener? Below, I’ve summarized my personal favorite aspects of the program—so far. And I say “so far” because the software has so much depth of capabilities and bells and whistles, I discover something new and even more fun every time I use it.

1. Love me a Trapper Keeper!

I am a true child of the 80s. When I took my kids back-to-school shopping earlier this fall, I teared up, grieving that they shall never know the true beauty of the Trapper Keeper. Oh, sure, we found imitation versions on the shelves, but nothing close to the ultimate office supply nerd’s dream machine contraption, which kept everything in check, even when the bully on the football team rounded the corner and flipped my books in the air, sending everything—including my fragile, Love’s Baby Soft ego—to the floor.

Well, never fear those bullies again. Scrivener is your virtual Trapper Keeper. The program holds everything you need for your novel—websites, photos, places to jot down random thoughts and ideas, references, and notations—everything. And since it’s all in one location, nothing falls out.

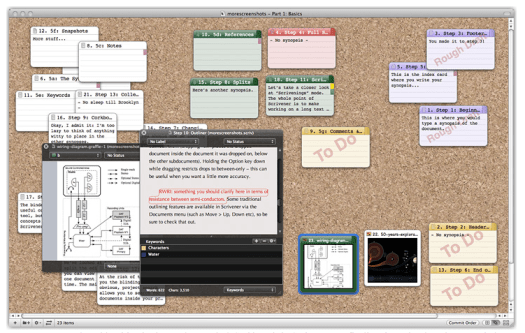

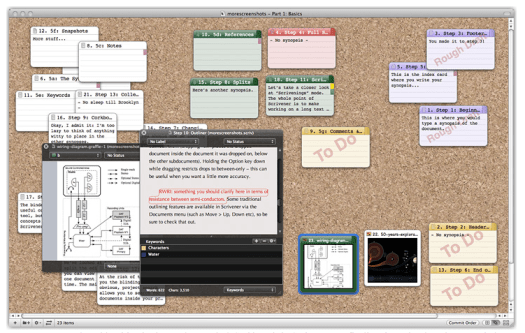

2. The corkboard is adorable.

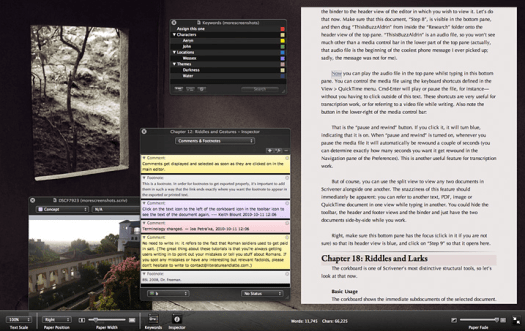

Say good-bye to sticky notes falling on the floor when it gets humid outside. Say hello to the floor you haven’t seen for months, since it’s been covered in index cards. Scrivener allows you to not only create virtual index cards and post them on a virtual corkboard, but you can also rearrange them, even when your manuscript is complete. Need to move chapter 30 back before chapter 14? No problem. Instead of scrolling back up and down through pages of text, just point, click and drag!

Better yet, each index card can function as a chapter synopsis, and you can attach various and individual scenes to each card, again, for easy viewing and rearranging, even within a chapter.

And as an added bonus, you can print out the index cards you create within the program, complete with lines to cut them the exact size of a 3×5 card.

As the website says, “Make a mess. Who said writing is always about order? Corkboards in Scrivener can finally mirror the chaos in your mind before helping you wrestle it into order.”

Don’t like index cards? That’s okay, because you can do your writing (also with rearranging capabilities) via the outlining mode.

3. Don’t just think about Harry Connick as you write out your protagonist’s next love scene. See him on the screen.

Don’t just think about the New York City skyline as your villain creeps through Central Park. Keep a photo of it on your desktop as you write.

Character, setting, and other research organizers allow you to attach photographs, charts, maps, and more all together and accessible as you write. One of my supporting characters looks like Matthew McConaughey. Seriously. He does. So whenever I need to jot down notes about his character, I open up my folder and there he is, gazing at me. Beautiful.

(woah–where did HE come from?!?)

(woah–where did HE come from?!?)

4. Worry about Word later.

It took me awhile to get over the fear of not writing in Word. But alas, the designers make it possible for you to compile all the text behind all those index cards and export it into one, seamless document which dovetails easily into Word.

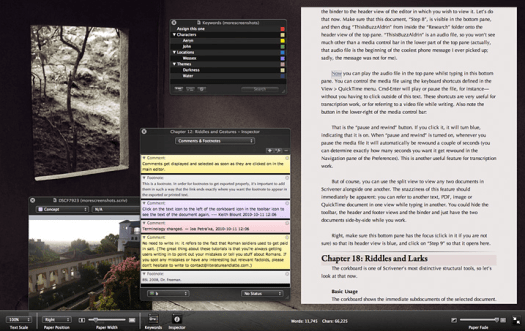

5. Other cool features I love:

- A name generator with every ethnicity and region imaginable!

- Templates

- Word count features, by chapter and whole document

- Color-coding for chapters, editing status, and more.

- Progress tracking

- Keyword options

- Formatting assistance

The website sums it up best:

“Most word processors approach composing a long-form text the same as typing a letter or flyer – they expect you to start on page one and keep typing until you reach the end. Scrivener lets you work in any order you want and gives you tools for planning and restructuring your writing. In Scrivener, you can enter a synopsis for each document on a virtual index card and then stack and shuffle the cards in the corkboard until you find the most effective sequence. Plan out your work in Scrivener’s outliner and use the synopses you create as prompts while you write. Or just get everything down into a first draft and break it apart later for rearrangement on the outliner or corkboard. Create collections of documents to read and edit related text without affecting its place in the overall draft; label and track connected documents or mark what still needs to be done. Whether you like to plan everything in advance, write first and structure later—or do a bit of both—Scrivener supports the way you work.

But wait. Before you buy, please note:

As with any computer program, there are negatives. Some folks–including an adorable and brilliant writer friend of mine–hate it. Also, while a PC version is available, the program was designed to operate on Macs, and the designers even admit it will probably work best on that platform. Try the trial version before you buy it to see if it will work for you and your computer operating system.

Also, you do need to have at least a smidge of computer savvy. And patience. There is a learning curve to this program, and the designers have been kind enough to offer a thorough, interactive tutorial and instruction book. While helpful, the program is so rich even I—a borderline computer geek—felt a little overwhelmed initially. And I don’t know if I’ll ever use all the functionalities.

That said, Scrivener has truly changed the way I approach my novel writing. I feel like it really frees my mind to focus on the prose, because I no longer have to remember where everything is on my hard drive . . . or if my dog ate a sticky note or a stack of index cards.

I honestly don’t know why more folks aren’t using and/or raving about the software.

Try it for free for 30 days.

I can’t throw in a set of steak knives, but I’d be willing to wager you’ll like the program, too.

Almost four years ago, I stood in an apartment parking lot with twenty-three strangers from all over the country. We made awkward conversation, silently sizing one another up and wondering how people so different would ever survive a semester together.

Almost four years ago, I stood in an apartment parking lot with twenty-three strangers from all over the country. We made awkward conversation, silently sizing one another up and wondering how people so different would ever survive a semester together.