7 Slippery-Slope Reasons Writers Shouldn’t Blog

Yes, I know. I am a writer and this is a blog post about not writing blogs. Irony is everywhere. Embrace it. But this topic still matters because many publishers urge authors to start and maintain a blog. Should you? Start the slope with me, then decide for yourself:

- Blogging can create a dopamine addiction, a Pavlovian instant-feedback dependence. Especially when you’re working on manuscripts that take a year or three; it’s a long silent drive with no one in the car. That immediate rush of reader response can derail the long obedience of writing (riding) patiently to a distant destination. And clearly, then…

- It also steals precious time away from long form writing and from writing articles with larger readerships and influence. Even if you only post once a week (as I do), even that can take the entire day, which means one workday out of five is gone. Not to mention the time taken to respond to every comment, which you absolutely should do.

- Because of this, and because you never have enough time to write, and because you know #1 and #2 are true, you will then decide to write your blog as efficiently as possible, which then means hasty pasty work that can degrade your artistry and your own standards of excellence. You blog to create a “brand,” but maybe your blogging “brand” tarnishes your book brand? But…

- It won’t matter and you won’t care because now advertisers are at your gate and you’re soon selling so much merchandise you realize you could do this full time with a few small adjustments to your editorial content and your wardrobe and your housewares, which you now feature because you’ve become such a commodity you spend most of your time taking photos and signing contracts rather than crafting paragraphs. Or…

- Just as easily, You become a political crankcase. Though you never plan this, the immediacy of blogging, the outrageousness of current politics and the catharsis you imagine awaits you after verbal tirades and blood-letting on your blog can oh-so-siren-song you into becoming a self-righteous rant-er in your beloved space which you once intended for the literary care and feeding of others. It will happen so gradually you won’t even notice until eventually…

- You will see yourself as a social/medical/educational/historical/everything commentator as knowledgeable about every current hot issue as the next guy and, armed with opinions you no longer want to waste, you deputize yourself and spend your energy preventing the demise of the free world or whatever your current passion has become now that you’re a Truth-warrior and Word-slinger rather than a writer. But also, you could slide the other way and…

- Care so much about your readers who are themselves tired of the sensationalized fake-newsy rants of the blogosphere that you spend your time devising outlandishly clever posts that occasionally include YouTubes about goats to prod your weary readers into liking and sharing your freakish brilliance. In other words, you’re writing simply for their attention rather than writing about what you really care about which doesn’t work at all, Or it does work and because you now have 50,000 followers, you decide to run for political office or move to L.A. to try stand-up comedy. Failing in both, you move back in with your parents and get a job designing slipper socks. You forgot you ever wanted to write.

You could end up here OR, you could slide another way and discover that life is strangely riddled with holiness and your weekly posts press you to find the divine you might otherwise miss. And around those words a collection of strangers begins to gather into neighbors you soon love who join you in this weekly act of holy listening. And before you know it seven years have gone by and you know many by their names and this wondrous crazy life now belongs in some way to all of you. And you may sell more books or you may not, you don’t keep track because you’re too busy writing and writing and all you know is you never want to stop.

Should you blog? You decide.

10 Secrets from the Weird World of Writers

You already know writers are strange. There’s your great-aunt who wrote a whole series of children’s stories about a one-eyed pirate she named Captain Crunch. Okay so far, but–Captain Crunch was a carrot. Yes, a pirate carrot. (And she put an eyepatch and a boot on the poor vegetable, too, didn’t she?)

And then–what about Writer’s Workshops? How can people pay good money for the torment of writing, you wonder. And what do they do–sit around and diagram sentences, argue over the proper use of the dash, fist-fight over the relentlessly contentious comma?

You know they’re strange. But let me help untangle this mystery. I’ve taught writing and led writing workshops for thirty years. So here it is, the inside scoop, Ten Secrets from the Weird World of Writers

Secret #1

Writers are scared. We always write alone. Now we are gathering with twelve or more to share a house, an island and a week together? We know it could go badly. The others could be bored with the stories from our lives. There could be tussling for the best seat. There could be wrangling for compliments and attention, for approval. Factions could form. Conversation could turn to Trump-ish Tower-building babble. Can we really do this?

Secret #2

Writers are brave because they go anyway, fears and all. Because we know that even if it goes terribly wrong, even if it turns tragic, at least we’ll have something to write about.

Writers are scavengers like that. Even carrion can look good under our gaze and pen. We value what others don’t. We look for the discarded, the buried, the wounded. Our words take us there. And when we find them, these poor bodies and souls, memories, aunts, accidents, deceits, griefs, we attend with oil and wine. Who knows what might return to life?

Secret #4

Writers are ascetics who care about words (on the page) more than food, more than movies, more than chocolate, more than presidential debates, more than new boots, more than tropical beaches (unless it’s winter and we really do get to go.) Maybe you guessed this. But what you don’t know is: we care about words-on-a-page because we care even more about the writer who lived them, who wrote them in her own spit, sweat, blood and fears.

Secret #5

Writers are also gluttons. No, not for punishment–for food. We gather with one another, and we get fat. When our words and lives are heard, our lean and lonesome souls rejoice and dig in, scoop deep, and pile high. Because going away means coming home, and being heard and seen deserves at least a fatted calf. (Pass the herbed butter, please.)

Secret #6

Writers retreat from the world but they care about the world more than most. Writing is love-in-action for us. Our words, written in closets, take us deep into the smell of fresh laundry on the line, into the morning sun glinting off our sister’s headstone, remembering the taste of the paste we ate in first grade art class. Our own words lead us to love the world of laundry, dirt and matter better.

Secret #7

Writers are ignorant. We know we know nothing. We know in the madness of living we’ve missed so much of our own lives, not to mention others’. So we write to recover it. We write to remember… when our mother dropped our dinner on the kitchen floor because she couldn’t believe we won, when our friend with arthritis knit us a purple hat—and we lost it, that day we saw a girl in a pretty flowered dress carry a new toilet seat into the bus station, when we sat beside our dying father and he touched our wrist.

Secret #8

Writers don’t write to tell you what we know, we write to ask you if you care. We don’t have all the answers. Not even close. But we do have lots of questions about this human life we’re all trying to muddle through. And our biggest question is: do you care about this giant existence, and all the glorious and sometimes hideous details of waking up every morning in it? And will you come with me today for a few minutes so we can see and maybe name this thing called “life” together?

Secret #9

Writers know they’re weird. We know we bleed more, watch more, wonder more, stumble more, cry more, listen harder than others around us. We feel weak. We feel different. We feel less-than. We write to find out if this strange affliction can bring good to us and to others.

Secret #10

Writers are audacious. We have no idea when we write if two or twenty or twenty thousand will read our work. But we write anyway. We know some will judge us harshly, even renounce us, for the truths we write. But we write anyway. We know our work will not earn us much or even any money at all. But we write anyway. Against all reason, against all critique, against all loss, we keep setting words down on the page, one after another. The world is birthed new every minute. Someone must take notes!

Maybe it’s okay to be weird.

I know I’m in good company.

Do I HAVE to Be a “Christian Writer”?

For my first eight years as a publishing writer, I had a hot New York agent. She hung with me through high times and low—until the day I sent her my new manuscript, which was overtly faith-based. She dropped me like a potato on fire. I knew that would happen. But I had to obey God and offer explicit Scripture-based hope. Most of my subsequent books have done the same.

I never wanted to be a “Christian writer.” I never wanted to be confined to “Christian readers.” I wanted to write for ALL people, and I still do. But I also know my faith can turn people away. Here is our dilemma: how do we write the truth with integrity, yet speak to all people, regardless of faith? Here are some thoughts that guide me through the thorny “Christian Writers” thicket.

We need not tell all the truth about anything at any one time (even if we thought we knew it). Life, issues, experiences, even under the purview of God, are all complex, multi-layered, paradoxical. Communicating Truth and truths is a process that we engage in over a lifetime, encompassing many possible stages: plowing, sowing, watering, reaping. We need never feel that we have to roll out the entire plan of redemption in any one novel or memoir to make it “Christian.” There’s time. Think of your work as a body of work over your lifetime.

Though I want all people to know Christ, more, I want Christ to be made known.

Because he is found everywhere in life, in all places, in all things, I am not only freed but compelled to discover Him and make some aspect of His being known through twig, creek, moonrise, miscarriage, forgiveness, cyclone, salmon, burial, and supper.

Belief in Christ’s truth-claims do not narrow our art. Christians are accused of being “narrow-minded” because they subscribe to Christ’s radical and exclusive truth claims (“I am the way, the truth and the life. No one comes to the father but by me.”) Belief in this claim does not confine, exclude, or narrow our art: nothing and no one is more capacious, more inclusive, more imaginative, more original than Christ himself, who created all things, who is before all things, who binds all things together, who can be found in every cell of creation.

I intend to write only out of calling and passion. I seek that from God, not my agent, not the market, not editors, or even my publisher. This guarantees a wobbly path rather than a sure career. But, face it: there is no sure career in writing except the career of writing from faithfulness, obedience, and joy.

God’s truths are not just propositional and communicable by language: they are experiential, relational, incarnational. I desire to write from a faith that I am trying to live in and out of, rather than a faith I am simply pronouncing. Without lived-in faith, our words truly are noisy gongs. As Joy Sawyer has so brilliantly written,

“ . . . without an ever-increasing, tangible portrait of our God engraved upon our hearts, we reduce our proclamation of the gospel to the “clanging symbol” of language alone. Maybe that is why our message suffers so much when we rely upon mere rhetoric to communicate our faith: it’s simply bad poetry. Just as a poem can scarcely exist without images, we most fully express our poet-God by daily allowing ourselves to be crafted into the image of Christ.

I end here. I believe that writing is a calling, a kind of pilgrimage that takes us, like Abraham, from one land to another, through, of course, wastelands, where the promise of a promised land appears invisible and impossible—-but the writing inexorably, day by night, moves us closer to the city of God. And if we write well and true, we will not be traveling there alone. Others, at first reluctant, will slowly move with us, following our own feet and our words, drawn to the brightness of a city with open gates and lights that never dim.

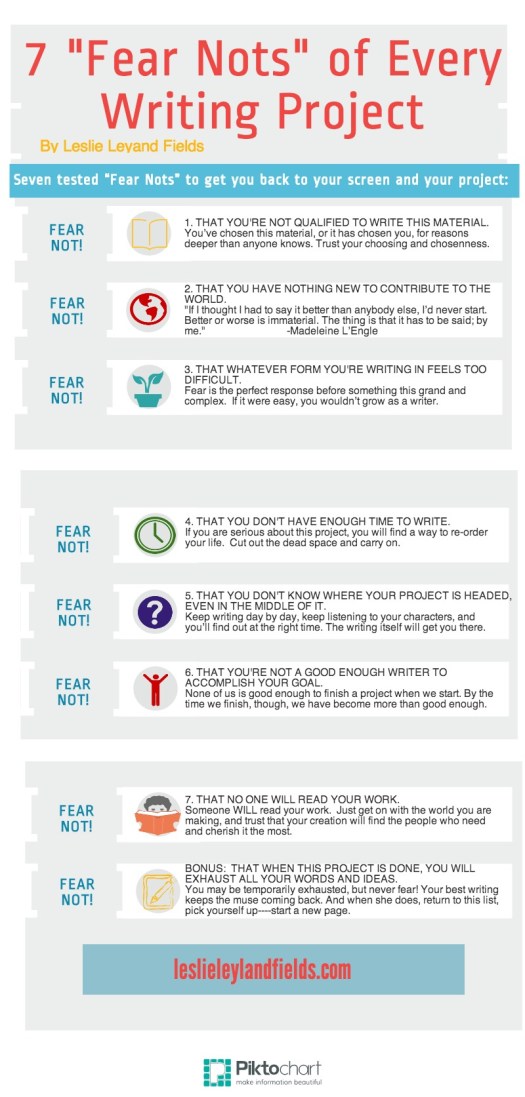

The 7 Fear-Nots of Every Writing Project

Whenever an emissary from another world showed up in all its effulgence, men and women fell down terrified, overcome, filled with God-brilliance and self-loathing. Our own writing projects, delivered by the other-worldly muse, can inflict and inspire a similar terror at times (Woe is me! Why did I think I could write this novel?). When you’re visited by these angels of brilliance-and-woe, (and you will be!), remember what usually came next, after the Visited fell facedown in the dirt: “Fear Not!” And then words of hope and direction were given to the stricken to lift them to their feet and their new purpose.

Here are 7 tested “Fear Nots” to get you back to your screen and your project:

1. Fear Not!—-That you’re not qualified to write this material. You’ve chosen this material, or it has chosen you, for reasons deeper than anyone knows, including you (unless you’re purely market-driven). Your desire, your interest, your life experience, your questions, maybe even your prayer life may have something to do with this insistent need to address this subject. Trust your choosing and chosenness.

2. Fear Not! —–That you have nothing new to contribute to the world. Listen to Madeleine L’Engle:

“My husband is my most ruthless critic. . . Sometimes he will say, ‘It’s been said better before.’ Of course it has. It’s all been said better before. If I thought I had to say it better than anybody else, I’d never start. Better or worse is immaterial. The thing is that it has to be said; by me; ontologically. We each have to say it, to say it our own way. Not of our own will, but as it comes out through us. Good or bad, great or little: that isn’t what human creation is about. It is that we have to try; to put it down in pigment, or words, or musical notes, or we die.”

3. Fear Not!—–That the article, short story, memoir, sonnet, sci-fi trilogy, whatever form you’re writing in, feels too difficult. Fear is the perfect response before something this grand and complex. This is partly why you’ve chosen it. If it were easy, you wouldn’t grow as a writer.

4. Fear Not!—–That you don’t have enough time to write. Of course you don’t. No one does. But if you are serious about this project, you will find a way to re-order your life: stop watching TV, write while the kids are napping, get up 2 hours earlier than everyone else, take your manuscript with you on vacation. Yes, it costs you ( and it costs others too, you must realize). Did you think otherwise? Count the cost to everyone. Then, if still so moved, cut and carry on.

5. Fear Not!—-That you don’t know where your novel, trilogy, even your memoir is headed. No one you know informs you of the outcome of their lives, do they? How many of your friends know where their lives are headed and how they will get there and who they will be once they’re there? You will not know this for your characters or story until they do. Keep writing day by day, keep listening to them, and you’ll find out what you need at the right time. The writing itself will get you there.

6. Fear Not!—–That you’re not a good enough writer to accomplish your goal. None of us is good enough to finish a project when we start. Some of us aren’t even good enough to start! By the time we finish, though, we have become more than good enough. The struggle, the long hours and the word-wrangling and prayer-wrestling will all get you there.

7. Fear Not! —-That no one will read your work. Someone WILL read your work. Maybe a few friends, the ones you really care about, maybe thousands of strangers. No one knows this when they are writing, and it has nothing to do with the writing. Just get on with the world you are making, and trust that your creation will find the people who need and cherish it the most.

BONUS: Because fears often multiply, one more to put to rest: Fear Not!—-That when this project is done, you will exhaust all your words and ideas. Not so. You may be temporarily exhausted, but never fear! Your best writing keeps the muse coming back. And when she does, return to this list, pick yourself up—-and turn a new page.

Don’t Let Anyone Shoot Down Your Moon

So you discover this morning from a reputable source that a grand nephew twice removed through divorce and adoption thinks your last book was second-rate and “whiny.” Worried, you decide to try therapy to make sure you’re not harboring ingratitude or a pathetic victim mentality. Or, as a cheaper option, you consider hiring an editor for your next manuscript to eradicate any possible language that might be interpreted as “victim-y.”

After this decision, which you feel good about, you get an email from a woman who says your last book is the best book she’s ever read and she wants everyone in the world to read it and would you send some more books with your autograph and maybe even a family photo? You breathe deeply, read the email over several times, and block off time to do this.

Later that day you hear that someone thinks the scarf you wore at last night’s reading was too retro and someone else thought you looked fat in that purple dress. Stricken, you drop the scarf in the trash, a bit sad because you did like it, after all, and at dinner an hour later, you eat only salad because you know it’s not just the dress.

While picking at your salad and checking your email, you discover that some friends are angry with you for not including them in your latest writing project and others who asked to be in your manuscript are bitterly complaining about their inclusion.

Saddened, you head to your seminar that night, after carefully choosing slimming clothes and a plain scarf. You speak with all the passion you have left after such a day and some people cheer and cry, and afterward a woman tells you you’re better than watching a movie, while an elderly man in the back row falls asleep in the middle of the most dramatic part.

And after many such days, you lie awake on your pillow finally knowing what the unforgivable sin is—or, rather, the unlivable sin, and you vow you will no longer do it, you will no longer commit the terrible sin of belief. You will no longer believe all the rumors of madness, the rumbles of inadequacy and girth, nor reports of laud and praise. You know they are all true in some way, and they are all false in some way as well, but mostly, you know they will kill you with redirection and indecision.

In such times, you dose yourself with Ann Lamott:

“Yet, I get to tell my truth. I get to seek meaning and realization. I get to live fully, wildly, imperfectly. That’s why I’m alive. And all I actually have to offer as a writer, is my version of life. Every single thing that has happened to me is mine. As I’ve said a hundred times, if people wanted me to write more warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

And this:

“My pastor said last Sunday that if you don’t change directions, you are going to end up where you are headed. Is that okay with you, to end up still desperately trying to achieve more, and to get the world to validate your parking ticket, and to get your possibly dead parents to see how amazing you always were?”

And you suddenly know it’s true: the world will not validate your parking ticket, so give it up and return to the life you’re supposed to be living. Your one “wild and precious life” given to you not to be hoarded but to be given away. And when you give it away, however kind you try to be and whatever form it takes, because the world is a crazy place, this will always be true: Someone is always waiting to shoot down your moon. Just know that some will be angry, some will bless you, some will betray you, some will be mean and small and some will be grateful and love you for life, till death do you part.

In all the betrayal, admiration, and lights, here is what you do:

You work at loving them all, and you keep on writing.

You will not be hushed, not by hurt or by hate; you keep on writing.

You will not keep trying to satisfy insatiable people; you keep on writing.

You will not listen to critics in the shadows, afraid of their own lives; you keep on writing.

You will not let praise erode your stability; you keep on writing (and rewriting).

Don’t let anyone shoot down your moon. Tell the truth. Please God. Love your neighbor. Love your enemies. And for the sake of us all,

Keep writing.

Don’t Write to Heal and Other Truths about Writing from Affliction

Dear writers, don’t we know already that we are to write into our darkest moments? My writing students have heard me say this 1000 ways: Enter the forest, dive into the wreck, face your toothy, hot-breathed dragons, open the closet, hold hands with your enemies, etc. We may remain silent in the midst of them, but at some point we must write. We must steward the afflictions God has granted us. Patricia Hampl reminds us why: “We do not, after all, simply have experience; we are entrusted with it. We must do something—make something—with it. A story, we sense, is the only possible habitation for the burden of our witnessing.” Dan Allender, in “Forgetting to Remember: How We Run From Our Stories,” tells us what happens when we ignore the hard events in our lives: “Forgetting is a wager we all make on a daily basis and it exacts a terrible price. The price of forgetting is a life of repetition, an insincere way of relating, a loss of self.”

How then do we begin to write from within our afflictions? And how might the practice and the disciplines of writing offer a means of shaping our suffering into meaning for both writer and reader? Forgive the brevity and oversimplification, but here’s what NOT to do and why:

1. Don’t write to heal. Really. Our therapeutic culture urges us to write into our pain as a means of self-healing. Newsweek’s article, “Our Era of Dirty Laundry: Do Tell-All Memoirs Really Heal?” rightly questions this cultural assumption. One friend assumed I wrote my most recent book, Forgiving Our Fathers and Mothers: Finding Freedom from Hate and Hurt primarily as a means of self-healing. Not so. Writing into our pain can be hellish at times. Know that returning to re-live an experience with language and full consciousness is sometimes worse than the original event. Recognize that writing into affliction brings its own affliction. And even more importantly, recognize that when we are predisposed to heal ourselves, we will not be fully honest in the writing. Healing will likely and eventually come, but only as we engage with the hardest truths.

2. Don’t write to redeem, to turn inexplicable pain into sense and salvation. We want to bring beauty from ashes. We want to make suffering redemptive to prove its worth. But this is God’s work, not ours. Our first responsibility is to be true to what was, to witness honestly to what happened. Our job is not to bring beauty out of suffering but to bring understanding out of suffering. Poet Alan Shapiro argues that “…the job of art is to generate beauty out of suffering, but in such a way that doesn’t prettify or falsify the suffering.”

3. Don’t write for yourself alone. This is not just about you. You are working to translate suffering to the shared page. Buechner reminds us of the universality we should be striving for: “…all our stories are in the end one story, one vast story about being human, being together, being here. Does the story point beyond itself? Does it mean something? What is the truth of this interminable, sprawling story we all of us share? Either life is holy with meaning, or life doesn’t mean a damn thing.” One of the greatest compliments I have heard from the book and the telling of my own story is, “You told my story.” Writing begins in the self but should consciously move us beyond ourselves, to place our story into the larger stories around us, and ultimately, into the grand story that God is writing. The most powerful work comes from a “self that renders the world,” as Hampl has said—not just the self that renders the self.

Life is holy with meaning. Pain is holy with meaning. Don’t miss it. I pray for you the strength and faith and wisdom to begin to enter those hard places and to translate your afflictions onto the pages we share—for the good of All.

How have you been able to translate your suffering into your writing?

The Slow-Writing Revolt

“Nice piece on that Huge Famous Blog, Allie,” you say to your friend, sincerely.

“Nice piece on that Huge Famous Blog, Allie,” you say to your friend, sincerely.

“Oh yeah, that thing. I just dashed that off, after two other pieces I wrote that day.” She tosses her perfect hair and regards her French nails.

“Really? How long did that piece take you?” you say, curious, but knowing you’re about to feel sick.

“Oh, about 37 minutes. Of course posting it all around the world took a bit longer. And then answering all the fan mail. That took about 3 days.”

“Yeah, I hate it when that happens.“ Weak smile trying to hide your nausea and the fact that it took you all day to write one short piece. You leave smiling, stomach roiling.

I confess: I have been Allie a time or three, but I’m mostly the other. Which is a problem. This week, for instance, I have four articles due in the next two days (Yes, this is one of them.) Not to mention a sermon to write, and three other presentations. It was the same last week. I’m not alone in this kettle of fish. A Facebook friend messaged me saying she couldn’t talk—she had three articles due that day. Others tell me the same.

So here we all are hunched over in emergency mode every day, madly chopping and grinding, tossing posts and articles and reviews out into the void. We’re generating twice as much content as we used to, in half the time.

What’s happening? We all have Facebook pages we’re trying to fill. Many have daily blogs they’re trying to fill. Surrendering that impossible task, now they’re filling them with other writers’ work. So now we’re all writing for our own blogs, plus our friends’ blogs, plus all those other publications we want to be in. And the book we’re writing? Oh yes, we’ll get to that, as soon as we finish this last little post. Behind all this is fear . . . a lot of fear. That we’ll disappear if we’re not on stage all the time. That we’ll be forgotten. That we’ll be invisible. That our platform won’t be big enough. That we won’t land another book contract.

Enough. I’m about to revolt.

Here’s what I’m preaching to you and me today. And I’m sorry I’m not saying it beautifully or lyrically with a grand metaphor that lights it all on fire. That’s what happens when you write too fast. Here’s the message: Slow down. M a r i n a t e. Wait. Sometimes even—-stop. Sometimes even—-say No.

We’re losing our way when nothing matters but the deadline. We’re losing our way when nothing matters but the byline. We’re wasting words. Sometimes we’re writing junk we don’t mean. Sometimes we’re just writing junk. We need to quit saying yes to people just because we want to fling a new piece out into the world for its five minutes of fame, if we’re even that lucky. Write to raze hearts and inflame lives. Mean every word you say. Stake your life upon it. Make your words worth every minute of your reader’s time. Anything less is ashes you have no time for and the world has no need of.

Take this, for example. I needed to write this in an hour, with a dash and a pinch of salt over my shoulder. Instead, against all intentions, I have taken three times longer. Not for the craft of it (apologies), but for the heart of it, which did not find me until the second hour. When we don’t give ourselves time to wander and to wonder, we’ll lose the truer words that want to be found and must be said.

Someday soon I hope the conversation will go like this:

“That was an amazing piece you wrote, Allie. You really nailed that review. I’m going to buy the book.”

“Really? That’s great! Yeah, it took me a week to write that. I just had to marinate in it for awhile.” She pulls at her frizzy hair and nibbles on her nails.

“Wow, a whole week! Good for you!”

“Oh, I don’t mean to brag or anything.”

‘No, that’s okay. That’s really inspiring,” you say. You think a moment, then blurt out, “You know, I’m going to ask for an extension on my essay. I think I need a little more time on it.”

“Of course! They’ll give it to you. You’re one of the best writers I know. They don’t expect you to be fast!”

Will you join me in this revolt?

Sentencing Ourselves to Pieces: Read a Whole Book!

I wrote an essay in my sleep last night–about books. Everyone in my dream was holding a book open, some paper books, some e-books, but all tilting their heads, reading thoughtfully. Books were not dead, the page would live on as a vital and treasured source of knowledge and experience. It was a good world. It was a good essay. It was a good dream. I kept pondering whether I should wake myself up to write it down. I did not, concluding that my slumbering self would surely remember an essay of this import.

I know what happened. I made the mistake of watching a 2010 documentary on the future of education just before bed, and paid particular attention to one interviewee’s prognostications about the book. Marc Prensky, the author of Digital Game-Based Learning, who describes himself on his website as an “internationally acclaimed speaker, writer, consultant and designer in the critical areas of education and learning,” says this about books and kids:

You don’t have to read them (books) to take in what’s in a book. . . If I said to kids, “You know, you don’t have to read all that much. But what I’d really like you to read are these few things and these excerpts, and these parts, and then I’ll tell you why you should read them. . . And no, you don’t have to pore through Silas Marner as I did in high school. There are very few books you have to have read.”

(I confess I would have been more willing to grant his pain in high school had he named The Brothers Karamazov or War and Peace. Silas Marner clocks in at a mere 200 pages.)

Let me understand this. If a writer’s work is truly important and excellent, it earns the exalted status of being pieced and excerpted. And then I wonder about the writers whose work rises to this esteem. How did they arrive at their insights, brilliance, and genius? Through an education built on carefully selected snippets?

We have forgotten why we read, I fear. We need information, yes. We need knowledge and discernment more. We need imagination far more. We need beauty and possibility even more. Without these, we are sentenced to a single spirit, a single mind, a single life.

This is what I used to say when books lay on every shelf and people at least aspired to read. We need to read whole books for far more important reasons now. College students can no longer attend to an entire lecture without Facebooking. We text through our meals, we interrupt our visits for every vibration in our shirt pocket. We finish very little single-minded or single-handed. We are sentencing ourselves to pieces, dividing our language, our hours, our very selves among multiple media, shrinking our thoughts into bits and tweets, excerpts and texts. We cannot attend. We no longer seek silence. We have lost our ground of being, and cannot remember what holds us together.

Last week I walked into a first grade classroom. The kids were sprawled on the floor, cross-legged on the carpet, leaning over their desks, all with a book in hand, faces inches from the page, intent. SSR time, Silent Sustained Reading. For twenty minutes every day. Were these the faces in my dream?

Maybe college classes can do the same. Maybe we can, as well. Silent. Sustained. Reading. Maybe we will remember back to first and second grade, why we read books then, from beginning to end. Why we write them. That slow immersion, that aching marinating in a world of such light, drama, and color, whose ending would bring delight, even wonder, and always an appetite for more. We always longed for more of the book, never less.

“Why are we reading if not in hope of beauty laid bare, life heightened and its deepest mystery probed?” asks Annie Dillard in her excellent book, The Writing Life. Why indeed? Why are we writing if not to do the same? But don’t stop reading with this quote. Read the whole book. Read as many whole books as you can. Sentence yourself again to beauty and whole-hearted delight.

So You Wanna Be Star? Join a Constellation!

At 10:30 pm this week, I discovered that the northern lights were ablaze. I learned this not by looking out my window, but by seeing photos friends had already posted on Facebook. And of course, some of the best photos were taken right in front of my house. Disgusted, and excited, I peered eagerly out my windows over the ocean for any faint remaining glimmer. Nothing. Not to be defeated, I proclaimed a “Northern Lights Search Party” and yanked my sons out of bed. (They were both still awake, reading sneakily by flashlight.)

We jumped into the car in various states of deshabille, and drove to the top of a mountain up a switchback road, passing–count them–30 cars on the narrow gravel passage coming down. The whole town was out tonight!

At the top of the mountain, beneath massive windmills, we scoured the black horizon for the shimmering waves of light–but saw only blackness, and then, something else. As our eyes shifted to night mode, they appeared, faint at first, then growing in intensity until we all gasped–a swimming sea of stars, like the night ocean alive with phosphorescence. Living on an island, under the heavy clouds of a maritime climate, we seldom see the stars. We bathed in their glory together for a long moment while the windmills strong-armed the sky overhead.

None of us are entire strangers to the stars. Every time we fling our book, our blog post, our music, our photographs out into space, we feel we’re launching a ship to the moon. We aim our hottest work, our sparkling, shattering words out into the universe, and then we wait. We wait for the world to come to us, to drive up the mountain to see us, to beckon to our dazzling light. We wait to become a star.

I would like to say I’m different, but I’m not. Somewhere inside even the most capacious heart, there’s a longing to be known. And outside the heart, our writing bosses command us to expand our platform. Inside and out, we begin to crave that far-off glittering goal, forgetting our real experience on the nights we gasp at the real cosmos. Those nights, save the sun, there is no single star that knocks us down. It is the panoply of stars that takes our breath. It is the collectivity of uncountable galaxies and star-clusters that lights the black sky and plows us down into worship and humility. It is their sheer density and magnitude that teach us our size, and then make us glad to be small.

We are small. We are one among millions of talented, smart, creative others. Lucky us–we get to learn from them all. And the whole world does not come to us. Just a few. But there still is so much gladness here: that we pursued ideas. That a journal has taken our story. That our blog made someone laugh. That we got to discover new truths. All this, good. All this, happy. Will there be more? Who knows! Just keep at it.

But listen closely. I am not saying dim your lights to take your small quiet place in the choir. Don’t be afraid to be brilliant and bold, to stake out your own corner. Don’t be afraid to question the lights already hung. But know, no matter how dazzling and original you are, you are surrounded by sizzling stars and a radiant moon that itself borrows light from another. Be glad of this.

Be glad of this. Yes, go ahead and shoot the moon. Aim high. Go ahead and hope you’ll be a star, but better, join a constellation.

I tell you true, when it happens that my own words hang among shining smart glorious beautiful writers and artists and thinkers and creators . . . there is little better joy. I am in awe of them all. They are my constellation. I’m happy that this little northern light of mine gets to wash in their light and shimmy and shine in their midst.